by Elizabeth Palmer

I don’t recall my own first day of school, but I do remember my older sister’s. As my mother walked Becky outside to the big yellow bus, I watched from the living room window. When my mom came back inside, she asked me if I would like to go to school too. She meant it in the general sense, as a rhetorical question. But I took her literally and was instantly overcome with a sense of dread. “No!” I answered emphatically. I knew that I was not old enough to leave my mother that day: my attachment to home, with its familiar toys and books, was too strong.

After about five minutes of playing alone that morning, I began to miss Becky profoundly, and I regretted having said no. If only I had agreed to go to school, my 3-year-old mind reasoned, I could be on the bus right now alongside my beloved sister, traveling to new adventures! Instead, I had chosen to stay at home with my mother, with the same old toys and books.

The dance of attaching and detaching

It’s a dilemma that all of us have gone through, this dance of attachment and detachment. We come into this world first physically attached to our mothers, in the womb and at the breast. Then we spend a childhood—or a lifetime—pulling away from our parents slowly, experiencing the simultaneous pain and excitement of becoming independent. We begin to attach to other people instead: friends, favorite teachers, a spouse, children of our own. We readily attach ourselves to objects: toys and books, the energy-efficient car, the perfect color of paint for the remodeled kitchen, the newest iProduct. And then there are the less tangible attachments that define us: the sense of identity that comes from our social and cultural location, the dreams that drive us forward in life, the desire for security and comfort.

It’s a dilemma that all of us have gone through, this dance of attachment and detachment. We come into this world first physically attached to our mothers, in the womb and at the breast. Then we spend a childhood—or a lifetime—pulling away from our parents slowly, experiencing the simultaneous pain and excitement of becoming independent. We begin to attach to other people instead: friends, favorite teachers, a spouse, children of our own. We readily attach ourselves to objects: toys and books, the energy-efficient car, the perfect color of paint for the remodeled kitchen, the newest iProduct. And then there are the less tangible attachments that define us: the sense of identity that comes from our social and cultural location, the dreams that drive us forward in life, the desire for security and comfort.

In the midst of it all, there is God—always closer to us than anyone or anything. Yet, on most days we tend to feel more attached to those things we can see and touch than we do to the God who reigns over heaven and earth.

I recently had the occasion to examine my own earthly attachments as my family went through the process of purchasing and moving into a home. As I visited houses that were on the market, I noticed all of the objects to which the homeowners had attached themselves—from the beautiful to the hideous—and I wondered about the memories that those objects held, unknown to me but precious to the owners.

A month later, packing up our own belongings for the move, I was able to view my family’s own household attachments with some objectivity. I was able to discern which items were no longer precious to us, and they went into the “donate” pile instead of a moving box. This process also gave me a fresh appreciation for the Christian Desert Fathers and Mothers of long ago, who gave up all of their earthly attachments to live alone in the wilderness and pray.

But even the Desert Fathers and Mothers, who detached themselves from all people, objects, and earthly comforts, still had dreams and theologies to which they were attached. They held fast to their visions and understandings of who God was calling them to be. And it was precisely because they held onto these non-tangible attachments that they were able to fulfill their mission of prayer and simple living.

Being entirely detached is neither possible nor an ideal to which God calls most of us. (As much as the introvert in me loves the idea of living alone in a remote location, it would be unhealthy for me after about a day. I would become lonely and self-focused, too far from the beautiful family and friends whom God has given me.)

The gift of the Eucharist

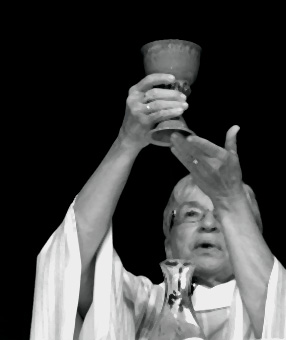

In fact, the gift from God that draws us each week into the life of Christ and connects us to the whole communion of saints is one that relies on tangible objects and the presence of other people: Eucharist. In a sip of wine, a morsel of bread, a word spoken, and the faces of those around us, we experience the healthiest kind of attachment—a rootedness in the One who creates, redeems, and sustains us.

In fact, the gift from God that draws us each week into the life of Christ and connects us to the whole communion of saints is one that relies on tangible objects and the presence of other people: Eucharist. In a sip of wine, a morsel of bread, a word spoken, and the faces of those around us, we experience the healthiest kind of attachment—a rootedness in the One who creates, redeems, and sustains us.

Our deepest earthly attachments, whether objects, people, or dreams, don’t need to be in competition with our relationship to God. Our attachment to God began in the moment that God began to knit us together in our mother’s womb and was sealed at our baptism. It’s nourished each week when we gather at the table to share bread and wine with our brothers and sisters in Christ. And it continues to grow throughout our lives, regardless of how we view our earthly objects, our relationships with the people around us, and the ideals that drive us. Attachment to God, after all, isn’t ours to accomplish—it’s a gift of pure grace.

But the choices we make regarding our earthly attachments are significant, because God calls and empowers us toward ethical living and self-sacrificial love. We should use the tangible things in our lives toward justice and mutuality. We should regard the people in our lives with a love that mirrors God’s love for us. We should hone our ideals and dreams in a way that fulfills God’s calling to us, living into our vocation with joy. In so doing, we will find that our attachment to God is at the very core of our identity. We will remember that we have been sealed by the Holy Spirit and marked with the cross of Christ forever.

Discussion questions

1. Which earthly attachments might God be calling you to give up?

2. What are some ways in which you can use your earthly attachments to live out your vocation?

3. When are the moments that you most keenly perceive your own deep attachment to God?

Closing prayer

Attach yourself to us, gracious God, so that we might better attach to one another. Give us wisdom as we discern how to negotiate the earthly attachments and detachments of this life. Give us courage as we attempt to live out our callings with integrity and joy. We pray in the name of your Son, who binds us together in mercy and love. Amen.

The Rev. Elizabeth Palmer serves as Lutheran Campus Pastor at the University of Chicago. She is currently very attached to her young daughters, Anna and Miriam.

The guys at our homeless shelter were talking about this very issue–being attached to God in the midst of troubles, when everything else has been taken away. Thank you, Elizabeth.

I’m grateful to have a picture of me accompanying this good message!

Thanks, Sue!

There is a lot of truth in what you say, Elizabeth. Thank you. I am studying Richard Rohr’s “Silent Compassion” and he reminds us that prayer is so much more than intercession, but actually, being open to find union with our LORD. It is really difficult to pursue a deepening faith life while being attached to so many other things that block the Spirit’s flow in our lives. I am trying to be more aware of the role all those things play in my life and rid myself of them when possible. It’s hard. The temptation is always there to acquire more. What a challenge!