by Sarah Carson

When I was a freshman in college, my roommate asked me to go with her to a popular new church in town. It was the mid-2000s, and I was used to getting dressed up for church on Sundays, singing hymns out of a hymnal, and listening to a preacher explain some five-point thesis he (emphasis on the he) had on an obscure passage from the Bible.

But at this church, we could show up in jeans and t-shirts—and so would the preacher. When we walked into the lobby, we were greeted with sunshine pouring in through floor-to-ceiling windows. A coffee bar next to the coat racks steamed milk and brewed espresso.

And when the ushers opened the sanctuary doors, a live band was on stage, fronted by a woman in tight-fitting jeans who belted out Martina McBride’s “This One’s for the Girls.”

Having grown up around hymnals and worship songs, hearing a country song sung from the chancel was mind-blowing. But the specific choice of the song—”This One’s for the Girls”—also left an indelible impression on me. It’s a song that not only celebrates women, but the complexities of the lives we live—our insecurities and social pressures, the fears and the challenges we have to overcome.

And since I’d already been living on “dreams and spaghetti-o’s” since my parents divorced when I was 12, the fact that God might want to also listen to those lyrics changed the way I thought about worship. It was a moment of expansion. Since then, I’ve compiled a long list of secular songs that sound like they’re being sung to God, even if they aren’t specifically being sung to God: “Unsteady” by X Ambassadors or even Shaboozey’s “Good News.”

Conversations with the Divine

Recently, I’ve had a similarly expansive experience with another form of spiritual communication: prayer.

This summer, I stumbled upon the work of a writer named Kevin Maloney. His books are rich with life and honest about love and human foibles. But if you’re a person who grew up in the kinds of churches I did, then the references to day-drinking and drug use in Maloney’s work might similarly make you feel like you should put down the book and repent.

His The Red-Headed Pilgrim, for instance, follows a young man who is trying to live a life in which he “prays without ceasing,” criss-crossing the country in pursuit of adventure and love.

The Red-Headed Pilgrim’s protagonist begins to pray without ceasing after reading the work of the Indian philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti. But Christians are also familiar with the concept from 1 Thessalonians 5:16-18: “Rejoice always, pray without ceasing, give thanks in all circumstances, for this is the will of God in Christ Jesus for you.”

And as I followed the Pilgrim’s journey from Portland, Oregon, to a Montana goat farm to selling teddy bears in Maine, I couldn’t help but think of all of the ways we might pray without ceasing, without actually praying with words in our minds or on our lips. I mean, if prayer means to be in communication with God, there are certainly ways we communicate with each other that don’t involve language. Maybe there’s a way to “pray without ceasing” in our actions and in our motives? Through dance? Through love of another? Through reading a book that touches your heart?

What is prayer for, exactly?

In their Living Lutheran article “Pray without Ceasing,” Kurt Lammi and John Potter explain prayer thusly: “Our praying does not change God. Instead, it is a way for God to change us.”

They point to Luther’s explanation of the Lord’s Prayer from his Small Catechism (Evangelical Lutheran Worship, page 1163). “If, as Luther said, God is going to do what God is going to do, even without prayer, then the only one being changed when we pray is us—and that’s a very good thing,” they write.

Prayer can help us better sit with our thoughts, express gratitude, or acknowledge our powerlessness in the face of a universe that is outside of our control. Studies also show that prayer reduces the heart rate, lowers blood pressure, improves sleep, and boosts immune function.

It has similar effects to yoga, meditation and the arts. Could these, too, be a kind of prayer? Perhaps a good stretch is a prayer for the body? Or a painting, a prayer without words?

Teach Us to Pray

When Jesus’ disciples asked him how to pray, he responded with the example of The Lord’s Prayer, which Luther broke into several major themes, including reverence for God, petitions for God’s help, repentance, and a commitment to live in accordance with God’s will for humanity.

When Jesus’ disciples asked him how to pray, he responded with the example of The Lord’s Prayer, which Luther broke into several major themes, including reverence for God, petitions for God’s help, repentance, and a commitment to live in accordance with God’s will for humanity.

If we were truly to pray without ceasing, perhaps we could see our daily habits and choices within these categories. When I stop and appreciate the sunlight through the leaves, I am living a prayer of reverence. When I honk at a stranger in traffic, I am sending a little prayer into the universe that we could all pay a little more attention to one another—and that I need help to chill out.

Isn’t the difference between a prayer and any other kind of communication its intention? If I choose to be intentional in my words and actions, I don’t think I can help but pray without ceasing. In my habits, in my routines, in the books I read, and in the music I listen to, I can choose to pray endlessly in whatever I do, wherever I am.

Discussion questions:

1. Name a time a book, song, movie—or something else!—spoke to you in a profound or meaningful way. What did it feel like? Did you see it as being connected to God?

2. What kind of prayer do you practice? Do all of your prayers have to include language? Why or why not?

3. What rituals or habits do you already engage in that might be considered prayerful

Closing Prayer

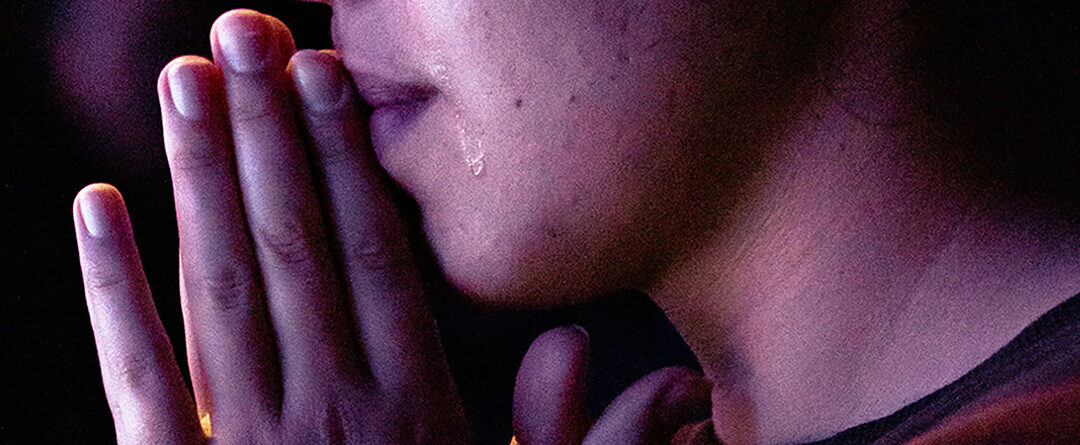

God of all, you speak many languages—not just English or Spanish or Hindi or Tagalog but the language of music, the language of love, and the language of math. Thank you for the myriad ways you’ve given us to communicate with you and to communicate with each other. In words and in pictures, in silence and in tears, may our conversation never end.

Sarah Carson is a former managing editor of Gather magazine. Her book How to Baptize a Child in Flint, Michigan is available where all books are sold. Read more of her work at stuffsarahwrote.com.

Sarah Carson is a former managing editor of Gather magazine. Her book How to Baptize a Child in Flint, Michigan is available where all books are sold. Read more of her work at stuffsarahwrote.com.

Read the other article in this issue by Sarah Carson.

Great thoughts. And writing.